Lithium mining: facts & figures you should know

Although electric cars make a significant contribution to climate protection, the mining of lithium for their batteries is often criticised. The debate focuses on the extraction of raw materials in the South American salt deserts. Here are some questions and answers for a more informed discussion.

How much lithium does the world need?

The global market for lithium, an alkali metal, is growing rapidly. Between 2008 and 2018 alone, total annual production in the major producing countries rose from 25,400 to 85,000 tons. A key growth driver is its use in the batteries of electric vehicles — but lithium is also used in the batteries of laptops and cell phones, as well as in the glass and ceramics industries.

Where is lithium available from?

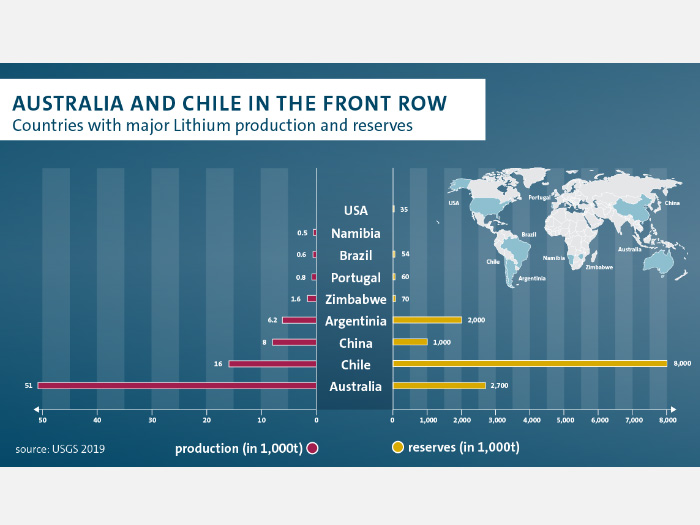

With 8 million tons, Chile has the world’s largest known lithium reserves, ahead of Australia (2.7 million tons), Argentina (2 million tons) and China (1 million tons). Within Europe, Portugal has a small amount of reserves. The total global reserves are estimated at 14 million tons, 165 times the production volume in 2018.

Where is the most lithium mined?

According to figures from the USGS (United States Geological Survey), Australia was by far the largest supplier of lithium in 2018, with 51,000 tons. Next came Chile (16,000 tons), China (8,000 tons) and Argentina (6,200 tons).

These four countries have long dominated the supply of lithium, with Australia overtaking Chile in recent years.

How do the mining methods differ?

Lithium from Australia comes from ore mining, while in Chile and Argentina lithium comes from salt deserts, so-called salars. In the case of salars, saltwater containing lithium from underground lakes is brought to the surface and allowed to evaporate in large basins. The remaining saline solution then undergoes further processing until the lithium is suitable for use in batteries.

Why is lithium mining criticised?

There are frequent critical reports on the extraction of lithium from salars. In some areas, locals complain about increasing droughts, which can threaten livestock farming or lead to vegetation drying out. According to the experts, it is still unclear to what extent the droughts are actually related to lithium mining.

And while it is clear that no drinking water is needed for the production of lithium, there are differing opinions as to how far the extraction of saltwater leads to an influx of fresh water and how that influences the groundwater at the edge of the salars.

More research is needed to assess this — for example, on the underground water flows in the Atacama Desert in Chile. In addition to lithium mining, there are other factors that could play a part. They include copper mining, tourism, agriculture and climate change.

How does Volkswagen Group obtain lithium?

Volkswagen Group works very closely with battery suppliers to ensure the use of sustainably-mined lithium in the supply chain.

Last year, the Group signed a memorandum of understanding with the Chinese lithium supplier Ganfeng, which obtains the raw material from several mines in Australia. Lithium from Chile is also used in Volkswagen’s electric models.

How does Volkswagen Group confront the criticism regarding lithium mining?

Volkswagen is currently working with independent experts on a fact-collecting mission to get a better understanding of the water supply in the Atacama Desert in Chile. As a matter of principle, all Volkswagen Group suppliers are contractually obliged to adhere to high environmental and social standards. The Group aims to ensure a sustainable supply of all raw materials, and this obviously also applies to lithium suppliers.

To this end, Volkswagen is also involved in initiatives such as the Responsible Minerals Initiative and the World Economic Forum’s Global Battery Alliance.

What are the long-term prospects for lithium demand?

Nobel Prize winner M. Stanley Whittingham, who laid the scientific foundations for the batteries used today, believes that “it will be lithium for the next 10 to 20 years”. At the same time, the number of electric cars is expected to rise sharply – Volkswagen Group alone plans to put some 26 million electric vehicles on the road by 2029.

However, in the long term, a large proportion of the raw materials used will be recycled, reducing the need for “new” lithium. This is unlikely to come into effect until 2030 though, when used batteries from cars at the end of their life span will be returned in large quantities.

Source: Volkswagen AG